Our first newsletter is now out. The newsletter is designed

to be essential reading for all inhouse

brand lawyers, providing

news, case updates and events in

the United Kingdom. This month, we

address 3D shapes and the latest

instalment in the Slush Puppie Wars.

Category: Uncategorised

-

Tapper v Beak Fried Chicken

Court: Appointed Person

Judge: Dr Brian Whitehead

Judgment: Here

Trade Mark: UK3380292, UK3120818, UK3815842, UK3849951

Issue: Trade Mark Invalidity

Summary

In Tapper v Beak Fried Chicken, the Appointed Person has provided guidance on when a party may resile from an admission, upholding Tapper’s appeal and remitting the matter to the Hearing Officer for consideration.

Trade Marks

Hearing Officer

The Hearing Officer heard two consolidated oppositions, Tapper’s opposition in relation to Beak Fried Chicken’s UK ‘842 and Beak Fried Chicken’s corresponding opposition in relation to Tapper’s UK ‘951.

The Hearing Officer concluded that Tapper’s opposition was successful under s. 5(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 and so the registration proceeded only in relation to “retail services relating to stationery, namely stickers”.

As to Beak Fried Chicken’s opposition, the Hearing Officer relied on an admission by Tapper in its TM8 counterstatement that the services in class 35 were identical with those for which UK ‘951 was to be registered. He concluded that, because the marks were visually similar to a medium degree, aurally identical and conceptually similar to a high degree there was a likelihood of confusion.

As a result, he refused registration for the certain services in class 35 including: “Advertising, marketing, promotion and / or retail … of key rings, pens, books on brewing beer, beer mats, etc.”

Appointed Person

Tapper appealed the Hearing Officer’s decision, arguing that the admission in its TM8 counterstatement was in respect only of the challenged services in the ‘842 mark.

The Appointed Person disagreed, finding that there was no ambiguity in the TM8 counterstatement, which read:

“The Applicant accepts that the word element is identical, however the Applicants mark has a strong and distinctive visual identity. The Applicant accepts that the services in Class 35 are identical.”

Tapper further argued that it was contrary to Registry practice and procedure for the Hearing Officer to continue on the basis of identicality when this was wrong as a point of fact.

Here, the Appointed Person disagreed with the appellants reasons, citing §4.1 of Contentious Trade Mark Registry Proceedings (2nd Edition):

“If an allegation is admitted, then that fact or matter is no longer in issue between the parties, and so (a) no evidence needs to be adduced to establish it; (b) no argument needs to be advanced to promote or defend it; and, (c) the tribunal need not trouble itself about it, as it becomes an agreed point between the parties and may be used by the tribunal as a basis for its decision”.

However, the Appointed Person found that the Hearing Officer had erred by not investigating with Tapper as to whether it wished to resile from the admission. He pointed to CPR 14.5, which explains that a Court can give permission to withdraw or qualify an admission. In doing so, the Court should consider:

“(a) the grounds for seeking to withdraw the admission;

(b) whether there is new evidence that was not available when the admission was made;

(c) the conduct of the parties;

(d) any prejudice to any person if the admission is withdrawn or not permitted to be withdrawn;

(e) what stage the proceedings have reached; in particular, whether a date or period has been fixed for the trial;

(f) the prospects of success of the claim or of the part of it to which the admission relates; and

(g) the interests of the administration of justice”.

As a result, the Appointed Person remitted the matter to the Registry for consideration of whether Tapper should be permitted to resile from or qualify the admission of identicality of services made in its TM8 counterstatement

-

Elbisco v Kerangus (BL O/0111/25)

Court: Appointed Person

Judge: Philip Harris

Judgment: Here

Trade Mark: UK00003651180

Issue: Trade mark validity

Summary

In Elbisco v Kerangus, the Appointed Person has upheld the Hearing Officer’s decision that Kerangus’ application for UK00003651180 (below) in classes 29 and 30 should not be registered in light of Elbisco’s earlier registration UK00003255468 (also below) in class 30.

The decision provides a useful analysis of the average UK consumer’s approach to signs with Latin and non-Latin letters (in this instance Greek).

Background

On 4 June 2021, Kerangus applied for UK ‘180 in classes 29 and 30, including certain food products. Some six months later, Elbisco opposed the application relying on its earlier right, UK ‘468, registered for class 30, again including certain food products.

In response, Kerangus defended the opposition and commenced a cancellation action. Here, it challenged the validity of UK ‘468 (which includes the words απλά and APLA) on the basis of its earlier registration UK0003700115 (which includes a stylised version of απλά), depicted below. UK ‘468 was registered in classes 29 and 30 for certain food products.

In both instances, the parties relied on s. 5(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994.

Hearing Officer

The proceedings having been consolidated, the Hearing Officer concluded that:

- The vast majority of average UK consumers would not understand Greek characters;

- As a result, the average consumer would deem Kerangus’ ‘115 mark to comprise the word element ANNA (not απλά);

- Further, the average consumer would consider the dominant element of ‘468 to be APLA (as απλά would not be readily articulable by the consumer);

- As a result, ‘115 and ‘468 were visually and aurally similar to only a very low level and conceptually different;

- While the goods for which the respective marks were, in part, identical or similar, given the lack of similarity of the marks, there was no likelihood of confusion;

- By comparison, the Hearing Officer held that, where APLA was the dominant element of both ‘468 and ‘180, they were visually similar, aurally identical and conceptually neutral;

- Where the goods were, in part, identical or similar, there was a likelihood of confusion;

- It followed that UK ‘468 remained valid, but UK ‘180 was not in relation to certain goods.

Appointed Person

Kerangus appealed on several grounds, including flaws in the assessment of the overall impression of the marks, visual and aural comparison, and likelihood of confusion.

Where the grounds of appeal were primarily a submission that the Hearing Officer’s assessment was wrong in fact, not law, the Appointed Person was unwilling to deviate from the Hearing Officer’s conclusions.

In particular, the Appointed Person emphasised that an appeal is by way of review, not re-hearing. This was recently summarised by the Court of Appeal in Lidl Great Britain Ltd v Tesco Stores Ltd [2024] EWCA Civ 262, where Arnold LJ as follows:

“110. It is common ground that, in so far as the appeals challenge findings of fact made by the judge, this Court is only entitled to intervene if those findings are rationally insupportable: Volpi v Volpi [2022] EWCA Civ 464, [2022] 4 WLR 48 at [2] (v) (Lewison LJ). Equally, it is common ground that, in so far as the appeals challenge multi-factorial evaluations by the judge, this Court is only entitled to intervene if the judge erred in law or principle …”

The appropriate approach to be adopted by the appellate court was summarised in Axogen Corporation v Aviv Scientific Limited [2022] EWHC 95 (Ch):

“24. Although I was referred to numerous cases on the subject …. the approach of the appeal court to a statutory appeal under section 76(1) of the TMA is uncontroversial. I bear the following principles, relevant to the issues before me, firmly in mind:

i) The appeal is by way of a review, not a rehearing;

ii) The appeal court will allow an appeal where the decision of the lower court was “wrong” (see CPR 52.11). Neither surprise at a Hearing Officer’s conclusion, nor a belief that he or she has reached the wrong decision suffices to justify interference;

iii) The decision of the lower court will be “wrong” if the judge makes an error of law, which might involve asking the wrong question, failing to take account of relevant matters or taking into account irrelevant matters. Absent an error of law, the appellate court would be justified in concluding that the decision of the lower court was wrong if the judge’s conclusion was “outside the bounds within which reasonable disagreement is possible”;

iv) The approach required by the appeal court depends on a number of variables including the nature of the evaluation in question. There is a “spectrum of appropriate respect for the Registrar’s determination depending on the nature of the decision”, with decisions of primary fact at one end of the spectrum and multi- factorial decisions (of the type which the parties agree were made in this case by the Hearing Officer) being further along the spectrum.

v) In the case of a multifactorial assessment or evaluation, involving the weighing of different factors against each other, the appeal court should show a real reluctance, but not the very highest degree of reluctance, to interfere in the absence of a distinct and material error of principle. Special caution is required before overturning such decisions.

vi) An error of principle is not confined to an error as to the law but extends to certain types of error in the application of a legal standard to the facts in an evaluation of those facts. The evaluative process is often a matter of degree upon which different judges can legitimately differ and an appellate court ought not to interfere unless it is satisfied that the judge’s conclusion is outside the bounds within which reasonable disagreement is possible;

vii) Another variable to be taken into account will be “the standing and experience of the fact-finding judge or tribunal”. Expert tribunals are charged with applying the law in the specialised fields and their decisions should be respected unless it is quite clear that they have misdirected themselves in law. Appellate courts should not rush to find such misdirections simply because they might have reached a different conclusion on the facts

viii) The appellate court should not treat a judgment as containing an error of principle simply because of its belief that the judgment or decision could have been better expressed; “The duty to give reasons must not be turned into an intolerable burden”. The reasons need not be elaborate. There is no duty on a judge, in giving her reasons, to deal with every argument presented by counsel in support of his case. It is sufficient if what she says shows the basis on which she has acted. The issues the resolution of which were vital to the judge’s conclusions should be identified and the manner in which she resolved them explained.

ix) In evaluating the evidence, the appellate court is entitled to assume, absent good reason to the contrary, that the first instance judge has taken all of the evidence into account.

It followed that ‘468 was valid, but ‘180 was invalid for certain goods.

-

Essity Hygiene v EUIPO (T-434/23)

Court: General Court

Judges: Kowalik-Bańczyk, Hesse and Ricziová

Judgment: Here

Trade mark: EU016709305

Issue: Trade mark validity

Summary

In Essity Hygiene v EUIPO, the General Court has upheld the EUIPO Board of Appeal’s decision to refuse registration for a leaf, depicted below.

The application was for class 16, including “paper, cardboard; fine paper, writing paper”, etc. The court reasoned that the average consumer would understand a leaf to refer to the ecological characteristics of the goods or to be purely decorative or ornamental.

-

![Abbott Diabetes Care v. Sinocare [2025] EWHC 206](https://brandinterchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/img_0276.jpg?w=1024)

Abbott Diabetes Care v. Sinocare [2025] EWHC 206

Court: Business & Property Courts, Chancery Division, England and Wales.

Judge: Mr Justice Richard Smith

Judgment: Here

Trade Mark: UK3779922

Issue: Trade mark infringement and validity

Summary

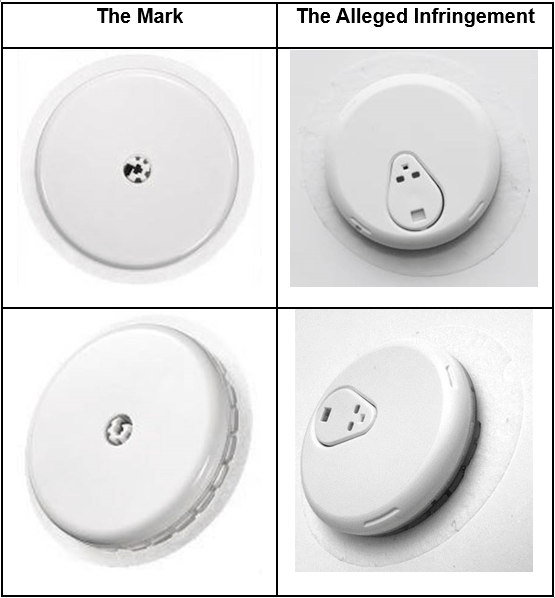

In Abbott v Sinocare, Mr Justice Smith has found Abbott’s three-dimensional trade mark to be invalid and not infringed.

The judgment provides a useful summary on the law as it applies to three-dimensional trade marks, as well as the use of evidence such as surveys.

Background

Abbott manufactures and sells a continuous glucose monitor, which works via an on-body unit, which inserts a small electrochemical sensor under the skin to measure glucose levels in the interstitial fluid around the cells. In December 2022, it registered a three-dimensional trade mark for its ‘on-body unit in class 10.

In April 2023, Sinocare introduced its own continuous glucose monitor, including an ‘on-body unit’. The following year, in February 2024, Abbott commenced proceedings, alleging trade mark infringement on the basis of s. 10(2)(b) and 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, as well as passing off.

In response, Sinocare denied infringement, advanced a defence under s.11(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 and counterclaimed that the trade mark was invalid on the basis of, among others, s. 3(1)(b) and 3(2)(b).

Initially Abbott sought interim injunctive relief, but this was broadly declined by the Court following certain assurances from Sincocare. The claim went to trial some 8 months from issue, with judgment given some four months thereafter.

Decision

R. Smith J concluded that Abbott’s trade mark was invalid, holding that it lacked distinctive character and that some of its characteristics were necessary to obtain a technical result.

As to the former, Abbott relied on survey evidence as well as evidence of marketing, advertising and sales to show acquired distinctiveness. The judge concluded that found that this was insufficient to show that the average consumer understood the mark to connote origin. In so doing, he was critical of the surveys (as to which, please see below).

With regard to the latter, the judge concluded that characteristics such as the flat, circular shape, outer adhesive area, the smooth texture and curved edges and central cogwheel all performed a technical function.

In any event, he concluded that there was no likelihood of confusion, unfair advantage or detriment. In doing so, he noted that the level of attention from the average consumer would be high, given the nature of the medical device. He also observed that there was a lack of evidence of a change of the economic behaviour of the consumer.

Comment

Trade mark law is generally sceptical of three-dimensional marks, with the trade mark owner having to meet a high evidential burden to show acquired distinctiveness.

This is exacerbated in the UK, where it is long established that it is difficult to obtain permission for survey evidence before the English courts and, when permission is granted, the court will treat these surveys with scepticism.

In particular, the court judges the surveys against the Whitford guidelines, first set out in Imperial v Philip Morris [1984] R.P.C. 293. In the case at hand, the court concluded that the survey evidence did not meet guideline 3, as there was a lack of information as to the source of the samples. It followed that it was not possible to establish whether the people surveyed were a representative sample or not.