Case Name: Bargain Busting Ltd v Shenzhen SKE Technology Co Ltd & Ors

Citation: [2025] EWHC 1239 (Ch)

Court: High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, Intellectual Property List

Judge: Mr Justice Miles

Judgment: Here

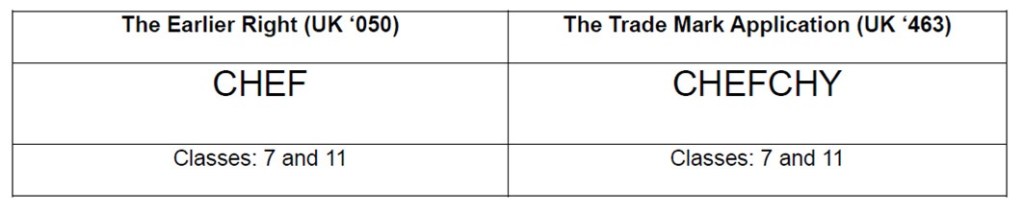

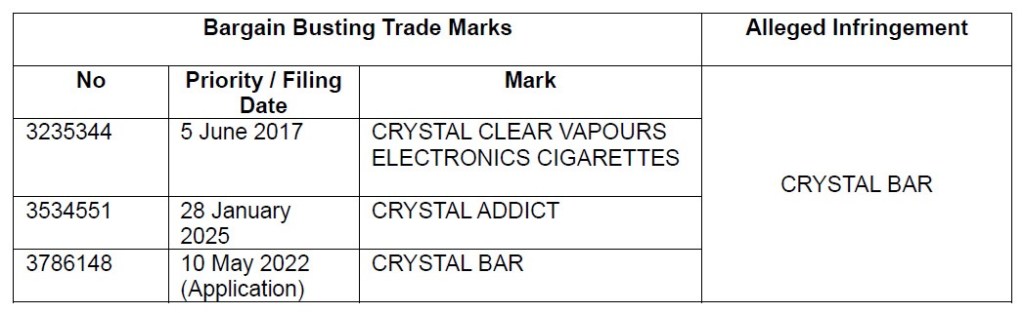

Trade Marks:

Summary

In Bargain Busting Ltd v Shenzhen SKE Technology Co Ltd & Ors, Miles J has granted an interim injunction preventing Bargain Busting from making threats against third parties for trade mark infringement. It serves as a cautionary tale to rights holders when making allegations.

Background

Bargain Busting owns several trade marks involving the word “CRYSTAL”. SKE is a Chinese manufacturer of e-cigarettes and vaping devices, marketed under the brand “CRYSTAL BAR”. Bargain Busting initiated multiple proceedings against SKE and others for trade mark infringement. SKE denies infringement and counterclaims that the trade marks are invalid.

The claim was commenced in September 2024. During the course of proceedings, in December 2024, Bargain Busting sent letters to eleven distributors and retailers of SKE’s products, alleging infringement and demanding undertakings to cease sales. SKE argued these letters were actionable threats (sometimes referred to as groundless or unjustified threats) and sought an interim injunction to prevent further such threats.

The law

The law of actionable threats was developed to address the practice whereby rights holders made spurious threats of proceedings against retailers as a result of them selling allegedly infringing products. Typically, rather than defend the threat, the retailer would withdraw the allegedly infringing product from the shelves, in the knowledge that it could stock an alternative (non-infringing) product. This would cause the supplier of the allegedly infringing product to suffer loss, without any recourse against the rights holder making the spurious allegations.

As a result, legislation was introduced (for trade marks, currently section 21 of the Trade Marks Act 1994) which entitles an ‘aggrieved party’ (for example, the supplier of the allegedly infringing product) to bring a claim for actionable threats, seeking an injunction preventing such threats and recovery of its loss.

To obtain an interim injunction, the applicant must show that there is a serious issue to be tried and that the balance of convenience favours the applicant. Typically, this is a high threshold to meet with the courts favouring the status quo unless it can be shown that the applicant is likely to suffer irreparable harm. If an interim injunction is to be granted, the applicant must provide a cross-undertaking to address any loss which the respondent suffers as a result of the interim injunction being incorrectly granted.

In this instance, Bargain Busting also asserted that Art. 10 of Schedule 1 (freedom of expression) of the Human Rights Act 1998 was engaged and raised objections under section 12 of the Human Rights Act 1998, which states that “[n]o such relief is to be granted so as to restrain publication before trial unless the court is satisfied that the applicant is likely to establish that publication should not be allowed”.

Decision

Considering the issues, Miles J concluded as follows:

• Bargain Busting’s letter constituted a threat of proceedings.

• SKE was an aggrieved party.

• SKE raised serious issues to be tried regarding the validity of Bargain Busting’s trade marks.

• SKE would not be adequately compensated in damages. In particular, Miles J reasoned that any damages would be difficult to quantify:

“I am also satisfied that if further threats were to lead to threatened parties to cease taking goods from SKE damages would be difficult to assess. While SKE would have information about its levels of sales to distributors or retailers, it would not readily be able to determine whether a falling off of sales through particular channels was the result of threats or of other market conditions. Other suppliers may gain market share through ordinary competition. The evidence shows that the vape market is very large and highly competitive. Unless customers who had been threatened by [Bargain Busting] told SKE why they had decided to cease or reduce their purchasers from SKE, it would find it hard to establish their claim for damages. Still more basically, SKE might not even learn that [Bargain Busting] had threatened particular customers with infringement proceedings. For these reasons it is likely to struggle to find evidence of the link between threats and losses.”

• Further, he noted that any damages could be substantial (SKE’s turnover in the UK had grown from $40.8m in 2022 to $405.6m in 2024). Bargain Busting, however, did not advance any evidence of its ability to pay damages.

• In turn, Bargain Busting could be adequately compensated by a cross-undertaking from SKE. In particular, the only potential loss which Bargain Busting was able to identify was a potential liability for costs for bringing infringement proceedings against parties without having been able to write a letter before claim in accordance with the pre-action protocol. SKE offered to pay £100,000 in to court, which would be adequate.

• The court accepted that Bargain Busting’s freedom of expression was engaged but found the interference minimal and proportionate. Bargain Busting could still make permitted communications and bring actual proceedings.

Comment

Actionable threats is a powerful (but often overlooked) tool. This is demonstrated in the case at hand. However, it has a wider role to play in relation to online takedowns. In particular, it has become increasingly common for rights holders to enforce their rights through online platforms (such as eBay and Amazon) using routes provided by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA) or equivalent. Here, the allegations will often be questionable, but the recipient does not have adequate recourse via the online platform to redress this. A claim for actionable threats may be the answer.